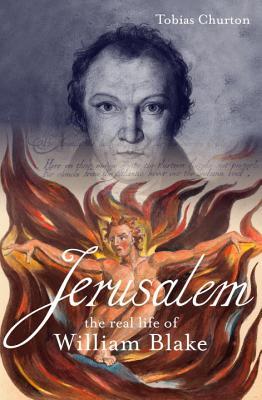

Jerusalem!: The Real Life of William Blake by Tobias Churton is a biography and a deep look at William Blake. Churton is a filmmaker who studied theology at Oxford. His documentaries include “The Gnostics” and “A Mighty Good Man,” a biography of Elias Ashmole. He is currently a lecturer on Freemasonry the Exter Centre for the Study of Esotericism, Exter University.

I started this book with the hope of learning more about William Blake, whose works, I admit, are limited to Songs of Innocence and Experience. I came to read that collection after hearing a musician include “The Lamb” on an album and joke on another that it was William Blake’s birthday so we should listen to his records. The musician was Patti Smith and she was also responsible for me picking up Blake as well as Rimbaud. I was impressed with Blake and, of course, wanted to learn more.

In the introduction, Churton spends many words talking about the epic poem “Jerusalem.” Its sudden popularity in England had some people thinking it was an important part of their national identity. I had expectations that this might be similar to The Most Dangerous Book about the printing of Joyce’sUlysses and Irish identity. However, this turns out not to be the case either.

William Blake had a problem which is a fairly unique among those who are famous. No one knew him. Blake did not keep or have a surviving journal. Most of his letters are lost. And, sadly, no one cared about Blake’s work until years after his death. People did care about his work in that he was a skilled engraver, but not as an important artist and poet. The only biography that existed was written by Frederick Tatham, who is discredited by Churton and others.

Jerusalem! begins with Blake’s death. Here there are several accounts of his passing. That, however, seems to be the most documented part of his life. There is virtually no personal information on Blake. In the absence of information, Churton does something intriguing. He creates a psychological and forensic profile of the artist.

Churton takes documented information such as addresses and places of employment and uses them to explain financial success and style of living. He goes further in detail with local and world events to form a picture of how these events would have influenced his life. Blake’s religious beliefs, Moravian Church, played a crucial role in his life. A lamb is the center of the church’s seal, perhaps an influence to “The Lamb” and “The Tyger.” Churton ties in Swedish philosopher Swedenborg with enough information to make him a secondary subject in this biography.

I usually tend to give the author the benefit of the doubt, however, in the introduction, Churton mentions the rock band The Doors and Blake’s influence on Jim Morrison. In the body of the book he mentions the song “Wild Child” and the seemingly out of place final line “Remember when we were in Africa.” Churton credits this to Blakes “Preludium to America.” Morrison, however, admired Rimbaud — who faked his death to escape fame and went to Africa to run guns. Morrison, likewise, spoke about disappearing to Africa and returning as Mr. Mojo Risen. Rimbaud has a deep connection with American artists like Morrison, Bob Dylan, and Patti Smith. There is more than a causal connection between Morrison and Rimbaud and little to none of Morrison and Blake. It may seem like a small error to many, but it is one that made me question other information in the book.

For a biography, I found it light on documentation. Granted much is inferred on little information. I felt I learned more about world events and those who influenced Blake rather than learning about Blake himself. I will admit the lack of the usual documentation makes it difficult to recreate Blake’s life. Churton’s approach is an interesting answer to the problem but leaves holes for criticism. Rather than I biography, I would consider this more of a psychological profile based on the historical limited information. I would think it would much more appeal to the scholarly crowd than the average biography reader.